MAIKE DINGER

What role might cultural activism play in a second referendum on Scottish independence? Journalist Chris Deerin predicts that any second Yes campaign would be characterised by ‘wearisome attention to detail, cold engagement with facts and, yes, a healthy measure of political cynicism’ – a stark contrast with the artistic enthusiasm which ‘bestowed glamour on the independence movement’ in 2014.[i] For many Yes supporters, in that burst of creativity it seemed anything was possible as long as it was imaginable. The hopeful, positive aura of the ‘cultural movement’ continues to shape the referendum in popular memory, despite suggestions that creatives’ messages had a limited social and geographic reach within the broader debate.[ii]

But the festivalisation of Scottish politics did not begin with National Collective, the leading body of ‘artists and creatives for independence’. In fact, the aim of National Collective’s ‘Yestival’ in 2014 – to showcase ‘a country that celebrates diversity and creativity […] with the desire and motivation to make a better future’[iii] – has clear echoes of an event held 24 years earlier.

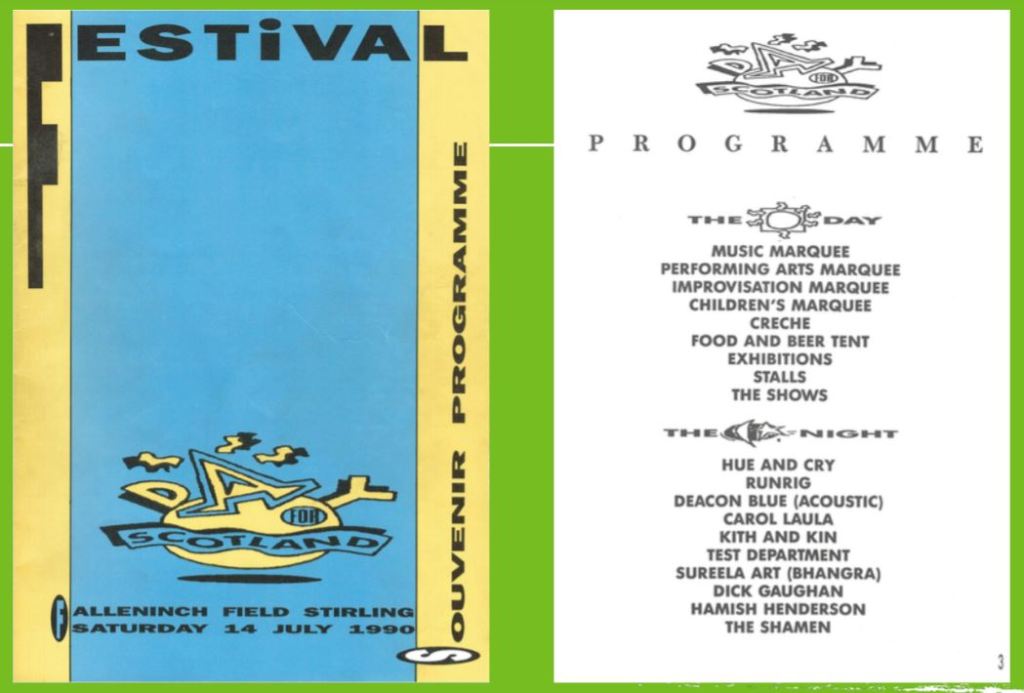

A Day for Scotland (ADFS) was a day-long festival of music and fun held in Stirling on 14 July 1990, and it invoked a similar image of the plural and hopeful nation. Local councillor John Hendry described the free, family-friendly event as

a unique opportunity for people of all ages, interests and backgrounds to join together in celebrating Scotland’s past and present achievements through music, drama, dance, comedy, sport, food and everything that is good about Scottish culture. But we are also looking ahead to a great new future for Scotland in the 1990s and beyond.[iv]

These aspirational themes reference a growing popular appetite for Scottish devolution, rather than full independence, but there are telling parallels between the two festivals.

The confluence of art and politics is a central theme in press coverage of the 1990 Day, with the Stirling Observer pleading to ‘Keep the politics out of festivals – enjoy the music’. Unlike National Collective’s activities, ADFS was publicly funded by taxpayers, and this brought a host of challenges and compromises. This was a central theme at the commemorative virtual event ‘A Day For Scotland – 30 years on’, held on 14 July 2020. Organised by the Scottish Political Archive at the University of Stirling, performers, pundits, punters and organisers of ADFS came together to excavate their memories and reflections.

Music critic Stewart Smith attended the event at the very start of his gig-going career, aged 9. If there were political overtones to the event, they went unnoticed as he drank in a range of exciting and unfamiliar sounds, from Test Department to The Shamen. His mother, literary scholar Lorna Smith, recalled

feeling part of a celebration of Scottish culture which seemed natural and unforced. There was an understated political narrative which in my memory was broadly left-wing but not in any way party political. It was a beautiful summer’s day and I remember the affection and respect shown to Hamish Henderson. We danced our way out of Falleninch Field to Runrig’s Gaelic version of “Loch Lomond”. A special day, the significance of which I didn’t fully appreciate at the time.

While ADFS – like the 2014 Yestival – might not have been party political, it made no secret of its enthusiasm for constitutional change. In the event programme, Pat Kane of Hue and Cry described the festival as ‘the largest meeting of Scottish artists under a commitment to self-determination’,[v] and Runrig’s Donny Munro cited ‘our basic right to self-determination’. The programme foreword by Campbell Christie, General Secretary of the STUC, ‘welcome[d] the role so many in the arts world have played in campaigning for constitutional and democratic change’, noting that ‘today we are celebrating our cultural heritage while demanding our democratic rights’, overtly linking the festival to the demand for the ‘establishment of a Scottish Parliament with wide-ranging powers’. Folk legend Dick Gaughan brought these themes together, writing:

Today is about music and the performing arts but it is about more than that – it is about art and struggle. Let today see the forging of an unbreakable alliance between the STUC, artists, and most important of all, you the audience, the people of Scotland […] to establish a Scottish Assembly as the next vital step in the defence of the Scottish people and towards us taking our rightful place among the community of nations.

Press coverage was broadly favourable, with the Stirling Observer noting that ‘speeches from the stage tended toward moderation rather than fanaticism’ while instilling a ‘real nationalist pride in the largely Scottish audience’ of 30,000.[vi] Another report, from Steve Fairweather, complained that so many statements on ‘rights, freedom and respect’ turned the event into ‘a political football’.[vii] Pat Kane countered that while ADFS was ‘a day for Scottish culture […] there is no way it could be called that without involving politics’.[viii] Despite the ‘political overtone’ of ADFS, journalist Stephen Smith agreed that you simply ‘had to celebrate’.[ix]

Unsurprisingly, the political dimension of the event met with opposition, including local ‘Tory attempts to sour the event with a campaign against the misuse of public money’.[x] Political historian and director of the Scottish Political Archive, Dr Peter Lynch, highlighted the political and economic insecurities which came with the event. Fears that Stirling Council could be fined for reckless spending (were the event to flop) were stirred by local Conservatives alongside broader complaints about the event’s lightly coded but unmistakable political aims. In Lynch’s view, the real significance of the festival was in using art and music to broaden the appeal of devolution, mobilising a large audience through a positive, future-centric approach at one remove from formal politics. And the event took place at a highly politicised moment, as several participants recalled, when Scottish popular anger against Thatcherism and the Poll Tax were reaching their peak.

In the festival programme, Elaine C. Smith alluded to ‘a government of another country [which] has done its worst to help destroy the core of our industry, attack our education service and our health service’. By contrast, ADFS would ‘celebrate what is truly ours’,[xi] placing national culture on centre-stage and (in Kane’s words) raising ‘the new Scottish Voice to a fever pitch’.[xii] Celebrating national pride on these terms drew a large audience into the festival politics of performing the nation – somewhat akin to an international football tournament – but in conditions where pro-Scotland symbolism carried extra constitutional significance.[xiii]

By 2014, the political and cultural realties had changed significantly. While in 1990 the focus was on civic goals of democratic representation, cultural activism was complemented by a clear – even fierce – rhetoric of national pride and self-assertion. By 2014, national culture and distinction were not felt to be threatened. In fact, the assertion of Scottish identity had been markedly depoliticised since devolution in 1999. Whereas ADFS was shaped by a call for cultural affirmation (‘of what is truly ours’), Scotland-centred politics were ‘normal’ and uncontroversial by the time of National Collective. Perhaps the embedding of a distinctly national political framework (in devolution) freed artists and creatives from their representative roles and burdens. If art and culture in Scotland ever worked as a substitute for political representation – as suggested by the ‘dreamers’[xiv] of the pro-devolution movement – this role was certainly altered by the establishment of the new Scottish Parliament. By 2014, artists and creatives were not called upon to fly the flag or defend ‘the Scottish voice’, precisely because these roles were now ‘baked in’ to the structures of devolved political culture.[xv]

Instead, National Collective provided alternative narratives of independence at a distance from the official SNP-led campaign, adding colour, passion and imagination to the case for Yes. It maintained a broad appeal partly by abstaining from politically radical thought and art and focusing instead on the ‘hopes and ambitions’ of the Scottish people as the unifying factor of the independence movement.[xvi] At the centre of this engagement was the invitation to the public to imagine their version of a future Scotland: through wish trees, knitting projects, poster competitions and Twitter takeovers.

One irony of the cultural activism of 2014 was the strong presence of nostalgia for an (imagined) past – without successfully accounting for the changed realities of the present. This tendency is evident in the theoretical framing of the culture-based activism, e.g. National Collective’s aim to offer ‘imaginative visions of a different Scotland [by] building upon the cultural gains of devolution’,[xvii] and the revival of culture-based campaigning formats, such as the Bus Party, which brought back activism and memories from the devolution campaign in the 1990s.[xviii] Broad gestures of national pride – though common in the wider Yes campaign – were replaced by predominantly small-scale creative exercises to inspire designs for a hypothetical country.[xix] Because of the binary nature of the referendum question and debate,[xx] many pro-Yes cultural arguments were heard mainly by the already ‘converted’.[xxi] Thus, the 2014 arts-based movement was not defined by assertions of identity but calls for different forms of civic representation and social and political accountability, coupled to imaginings of a different future. In general, both official campaigns in 2014 avoided overt arguments ‘from’ national culture,[xxii] and scepticism towards culture-based political activism was widespread.[xxiii]

This discussion lays bare the convulsion of politics and culture in the Scottish context: it links to the deeply engrained paradox of ascribing artists, and particularly writers, a vanguard role in national politics,[xxiv] while criticising political art for diminishing national culture (by selling out to politics). This practice gestures to larger continuities – and ruptures – in the Scottish independence discourse, namely a tendency to legitimate politics through culture-based activism based on nostalgia and national narratives of (self-) identification. My PhD research explores these themes further, exploring arts-based activism and the discursive mediation of ‘popular political participation’ during ‘indyref’ 2012-14. This project explores the political and media construct of a whole country engaged in creative debate and activism, despite quantitative media analyses indicating the marginal role of culture and identity in the wider debate.[xxv] Against this backdrop, my project contextualises the ‘different voices’ of the Scottish independence debate and explores how citizens chose to participate in creative grassroots activism, whose ‘voices’ were heard, and how artists and writers contributed through commentary and writing to the debate. (I am therefore very keen to speak with creatives, writers, journalists, activists, and campaigners about their experience and memories of indyref!)

Can we expect another artistic festival on national politics? Time will tell, but past experience shows us that art and culture have the potential to be much more than creative add-ons to a civic debate, based on their powerful legitimating function for various claims to political power (employed by different political parties, on different sides of the constitutional debate). The intrinsically political nature of national art and culture needs to be recognised, mobilised, and realised through cultural production rather than iterative commentary. There might still be space in the debate for the ‘dreamers’, but only if they succeed in promoting a shared dream to larger segments of society, and explore – both critically and creatively – the mobilising power of national art.

[i] Chris Deerin, “Hard to see where poetry will lie come second independence referendum,” Press and Journal (2 Feb. 2021), https://www.pressandjournal.co.uk/fp/opinion/columnists/chris-deerin/2863723/chris-deerin-hard-to-see-where-poetry-will-lie-come-second-independence-referendum/.

[ii] David Torrance, “Curious Case of Creatives Who Support Independence,” HeraldScotland (28 July 2014), https://www.heraldscotland.com/opinion/13172112.curious-case-of-creatives-who-support-independence/.

[iii] Mairi McFadyen, “More Than 30 Days, 1786 Miles, 16 Tents and One Carnival…How National Collective Took the Yestival all over Scotland,” HeraldScotland (3 Aug. 2014), www.heraldscotland.com/news/13173042.More_than_30_days__1786_miles__16_tents_and_one_carnival_____how_National_Collective_took_the_Yestival_all_over_Scotland/.

[iv] John Hendry, A Day For Scotland. Souvenir Programme (Stirling 1990), 5.

[v] Patrick Kane, Souvenir Programme, 13.

[vi] “Sunshine spectacle for all the family,” 1.

[vii] Steve Fairweather, “Keep the politics out of festivals – enjoy the music,” Stirling Observer (18 July 1990), 2.

[viii] Kane qtd. in Barr “Pat Kane and singer Fish,” 2.

[ix] Stephen Smith, “Happy crowds let the good times roll,” Stirling Observer (18 July 1990), 5.

[x] Linda Barr, “Pat Kane and singer Fish join in praise of big event,” Stirling Observer (18 July 1990), 2.

[xi] Elaine C. Smith, Souvenir Programme, 12.

[xii] Patrick Kane, Souvenir Programme, 13.

[xiii] Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism (London, Los Angeles, New Delhi, Singapore: Sage, [1995] 2010) 50-63.

[xiv] Scott Hames, The Literary Politics of Scottish Devolution: Voice, Class, Nation (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2020), iix.

[xv] See Hames, Literary Politics of Scottish Devolution.

[xvi] National Collective, “Making a space for a human conversation,” (7 July 2013), previously published in POST magazine, http://www.nationalcollective.com/2013/07/07/manifesto-imagine-a-better-scotland/.

[xvii] National Collective, “Making a space.”

[xviii] Libby Brooks, “Artists embark on ‘listening’ bus tour of Scotland before independence vote,” The Guardian (1 May 2014), https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/may/01/artists-bus-tour-scottish-independence-vote.

[xix] National Collective, “Making a space.”

[xx] Michael Keating, ed., Debating Scotland: Issues of Independence and Union in the 2014 Referendum (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2017).

[xxi] John McDermott, “Scotland’s Yestival Highlights “Bad Romance” with UK,” The Financial Times (1 Aug. 2014), www.ft.com/content/82d4627c-1989-11e4-8730-00144feabdc0.

[xxii] Donatella della Porta, Francis O‘Connor, Martín Portos and Anna Subirats Ribas, Social Movements and Referendums from Below. Direct democracy in the neoliberal crisis (Bristol, Policy Press University of Bristol, 2017), 34; 112.

[xxiii] Cal Flyn, “Scottish Independence: Aye, Have a Dream,” New Statesman (26 Sept. 2013), www.newstatesman.com/politics/2013/09/scottish-independence-aye-have-dream; Alison Campsie, “James MacMillan Likens Indy Group National Collective to “Mussolini’s Cheerleaders”,” HeraldScotland (26 Aug. 2013), https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/13119861.james-macmillan-likens-indy-group-national-collective-to-mussolinis-cheerleaders/.

[xxiv] Hames, Literary Politics, ix, 3-4.

[xxv] Marina Dekavalla, “Framing Referendum Campaigns: The 2014 Scottish Independence Referendum in the Press,” Media, Culture & Society 38, no. 6 (2016): 793-810, SAGE. https://doi:10.1177/0163443715620929

INDYREF: 5 YEARS ON is a free public event reflecting on 2014 and the ‘cultural debate’ in particular.

INDYREF: 5 YEARS ON is a free public event reflecting on 2014 and the ‘cultural debate’ in particular.

The final event in an extremely thought-provoking series of collaborative workshops on First World War civilian war trauma funded by the

The final event in an extremely thought-provoking series of collaborative workshops on First World War civilian war trauma funded by the