(Image © Adrian Hart, 2007)

EMILY ST.DENNY

Unsurprisingly, the debate over Scotland’s constitutional future has been forward-looking: projecting the nation as capable and deserving (or not) of political autonomy. But it has also drawn from an existing toolbox of meanings and representations, situating itself in a juncture between past and potentiality. Current debates clearly reflect the legacy of ‘new politics’ discourse emergent in the devolution campaign of the 1990s. Both campaigns, I would argue, are drawing lessons from the mitigated results of the ‘new Scottish politics’ in order to bridge the gap between their rhetoric and the political and economic realities facing Scotland.

Read in this light, the White Paper (Scotland’s Future) can be seen as seeking to establish a compelling equilibrium between aspiration and reassuring realism. Both the SNP and the broader Yes campaign are attempting to reframe the principles of ‘new politics’ as compatible with independence, rather than as the exclusive dividend of well-calibrated devolution within the union.

Devolution and ‘new’ Scottish politics

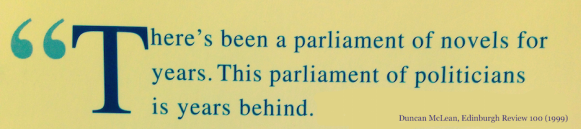

Talk of ‘new politics’ in Scotland was first associated with the campaign for the Scottish Parliament in the mid to late 1990s. At the time, most advocates of home rule, including many of the parties, civic groups and churches that made up the Scottish Constitutional Convention, emphasised ‘new Scottish politics’ as the potential dividend of devolution: a break from ‘old’ Westminster politics, considered by some to be discordant and divisive. The Labour UK government saw devolution as a means of enabling the development of appropriate Scottish responses to issues faced north of the border while fostering distinctiveness within the union. While the SNP also bought into the ‘new politics’ rhetoric, it presented the progressive potential of devolution as an improvement in the broader context of a continued effort towards full independence, which they argued to be the only means of bringing about a truly new Scottish politics. Overall, proponents of devolution presented ‘new Scottish politics’ as the positive culmination of new institutions, new policy processes and a new political culture.

While devolution has undeniably transformed the way policy decisions are made and implemented in Scotland, the extent to which it has delivered on its promise of new politics is contested. Most significantly, the institution of a Scottish parliament repatriated the debate and negotiation of policy in devolved areas to those they were due to affect. Indeed, the new Parliament was imagined as a forum for cooperative and constructive deliberation, supposedly in contrast to the adversarial House of Commons. This institutional development was wedded to the principles of consultation and civic participation, which the Scottish government has since extensively operationalised by involving local authorities, associations, unions and professional bodies in the negotiation and design of policy priorities. Additionally, the willingness of the main parties to cooperate, illustrated by the experience of the 1997 campaign on the devolution referendum, as well as their substantial overlap in policy matters and electorate, led many to believe a different, and more consensual, type of political behavior would become the norm.

The Scottish government has successfully realised some of the cornerstones of ‘new politics’. In particular, devolution led to significant changes in institutions and has certainly impacted upon the policy process. Nevertheless, the contrast between ‘new’ Scottish and ‘old’ Westminster politics has been overstated, and electoral competition being what it is – the intense and fraught vying for attention and support in a context saturated by adversaries and alternative ideas – inflated hopes of consensus politics have been somewhat frustrated. In this sense, devolution has not appeared to engender and embed a new political culture in Scotland. In particular, evidence would suggest that in the sixteen years since the Scotland Act established the Scottish Parliament, there has not been a significant move away from traditional adversarial politics. Rather than being the product of a putatively distinct political culture, cooperation in Scottish politics, when it happens, has tended to be the result of perceived mutual advantage or a shared goal.

Re-editing representations of Scottish exceptionalism

The representation of Scotland as different is not new. In fact, the myth of a Scottish exception pre-dates the debate over devolution and has recurrently surfaced throughout the period of the union. It is therefore not surprising that the inter/national debate over the upcoming Scottish independence referendum has re-edited the conversation over the possibility of new and different politics in Scotland’s near future. Indeed, this is an old discussion reinterpreted and reissued. What is interesting, however, are the emerging modalities of the most recent debate, with the Yes campaign vying to shift the framing of ‘new’ Scottish politics away from its connotations of fostering political and policy distinctiveness within the union and towards a broader discussion of sovereignty and democracy.

Scotland’s Future notably couches the constitutional future of Scotland in terms of democracy and progress. As such, the Scottish Government attempts to frame the discussion as one over issues of legitimacy, appropriateness and sovereignty, placing the representation of the stakeholders in the referendum at its heart. Rather than opting for a nationalist representation of the Scottish people heavily anchored on a purported cultural or ethnic singularity, the SNP has sought to put forward a case built on civic nationalism, whereby an independent Scottish state would derive its legitimacy from the expressed will of those who live and work on its territory. In keeping with the democratic principle of self-determination through participation, this general will is posited as being expressed through the making of decisions:

Decisions about Scotland – decisions that affect us, our families, our communities and the future of our country – should be taken in Scotland to reflect the views and concerns of the Scottish people, rather than by governments at Westminster with different priorities, often rejected by voters in Scotland. (Scotland’s Future, Introduction)

Interestingly, the act of making decisions on political and policy matters is presented as inherently worthwhile, separately from the act of making the right policy decisions. Thus, prefacing the White Paper, First Minister Alex Salmond states: ‘No-one is suggesting an independent Scotland would not face challenges. We would be unique is this was not the case. But we are rich in human talent and natural resources […] With independence, we can build the kind of country we want to be.’ In this sense, the challenges an independent Scotland would undoubtedly face are not rejected but owned, as the price and privilege of self-government.

This approach seeks to establish the viability and desirability of path-breaking political decisions in the context of significant uncertainty and risk. In this context the Yes campaign is faced with having to find an equilibrium between providing sufficient (and sufficiently compelling) information about how it would address the implications of independence, and setting out a case for autonomy liable to attract voters with a variety of policy preferences.

In Scotland’s Future the SNP has broadly resisted the urge to instrumentalise the White Paper as a definitive manifesto on what policies would look like in an independent Scotland – which would require the unpalatable hubris of projecting both a Yes vote in the referendum and the election of an SNP government in the first democratic elections penciled in for 5 May 2016. Instead, they opt to emphasise the role independence would play in opening up the twin realms of politics and policy to democratic design by those living and working in Scotland.

The document’s 670 pages lay out a relatively detailed vision of the policy options an independent Scotland could envisage, from free childcare provision to the re-nationalisation of Royal Mail, seen through an undeniably partisan lens. This strategy nevertheless aims to decouple the partisanship of policy preference, associated with electoral competition and routine politics, from the discussion of the future of sovereignty and legitimate representation in Scotland, considered above adversarial and short-termist party politics. Attempts are made to emphasise the democratic implications of, and policymaking opportunities afforded by, independence; these are discussed more prominently than the policy minutiae that would attend realisation of these opportunities. Correspondingly, broad principles that have become recurrently linked with representations of Scottish society, such as social justice, fairness and prosperity, are preferred over discussion of how each could be achieved through policy.

This effort to depoliticize the issue aims to place at a remove the political aspect of decision-making from the referendum debate, arguably to minimize its association with the perceived pettiness of politics at a time when trust in politicians has plummeted. While depoliticisation is a strategy associated with New Labour in the late 1990s, it did not emerge as an element of the debate over independence until recently and, therefore, cannot be considered an intrinsic aspect of the original ‘new politics’ discourse.

Unsurprisingly, in the context of vigorous campaigning for Scotland to remain within the union, and in the absence of similar blueprints setting out the modalities of possible increased devolution, this particular vision of Scotland’s future has met with widely contrasting responses. Thus, proponents of a Yes vote, such as Robin McAlpine (director of the Jimmy Reid Foundation) consider it a successful harmonisation of priorities and preferences in the context of a nation-building project supposed to enhance participation and representation regardless of partisan politics:

What I was looking for was a promise that between a Yes vote and the first democratic election in 2016, the SNP wouldn’t behave like it had the right to design a new country all by itself. The paper promises we will all get to play a part in writing a constitution and that its opponents will be included in the negotiating team that agrees the deal we get when leaving the UK. So I am reassured. (Jimmy Reid Foundation)

Conversely, critics, such as leader of the Better Together campaign, Alistair Darling, interpret this stance as a smoke-and-mirrors deflection tactic resulting in the failure to address key questions about how an independent Scottish government would set about achieving its naïve and nebulous goals.

In the 1990s, talk of ‘new Scottish politics’ was tightly tethered to the campaign for devolution and the establishment of a Scottish Parliament. This transformation was argued to hold the key to the development of new institutions, which would enable fair, inclusive and effective decision- and policy-making processes through which Scottish solutions to Scottish issues would be found, and ultimately would foster a consultative and cooperative political culture unlike the adversity held to characterise ‘old’ Westminster politics. Central to this argument were multiple and competing interpretations of a perceived Scottish difference. Scotland is different: her population’s problems and interests are different; the principles and priorities she is built on are different; the future she seeks for herself is different. Far from idiosyncratic, incantations of Scottish exceptionalism are a systematic fixture in debates over the nation’s political future. Unsurprisingly, with less than a year to go until the referendum on Scottish independence, the current debate has re-edited this tradition, merging old and new ideas and strategies, as the stakes are raised and Scotland’s constitutional future is reimagined once again. On the one hand, we see elements of the original ‘new politics’ discourse maintained; see the renewed interest in the possibilities an independent Scotland would afford the nurturing of a new political culture. On the other hand, elements such as the attempted depoliticisation of the democratic implications of the referendum have only recently been mobilised.

Overall, the white paper reframes the possibility of ‘new Scottish politics’ in terms of democracy and self-governance, and breaks away from traditional conceptions of representative and fair politics in Scotland solely as the reward reaped from effective devolution within the union. This exercise of projection and meaning-making seeks to navigate the obstacles presented by overwhelming uncertainty and staunch opposition – with very mixed reactions.

Emily St.Denny is a Research Assistant at the ESRC-funded Scottish Center on Constitutional Change, working as part of a team looking at policymaking in Scotland. She is also working towards a PhD in politics and public policy on the subject of contemporary French prostitution policy. She is based at the Division of History and Politics at the University of Stirling.